U.S. GOVERNMENT AND THE ART WORLD Spring/Summer 2017

BOOKS

1. WASHINGTON DC Wall Street Journal Native American Exhibitions

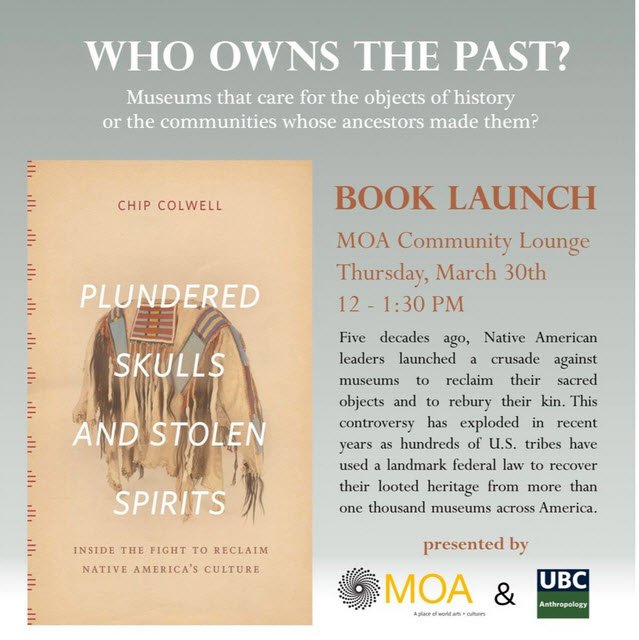

“When a white man’s grave is dug up, it’s called grave robbing. But when an Indian’s grave is dug up, it’s called archaeology.” Naomi Schaefer Riley reviews “Plundered Skulls and Stolen Spirits” by Chip Colwell.

By Naomi Schaefer Riley

Updated March 10, 2017 4:45 p.m. ET

‘When a white man’s grave is dug up, it’s called grave robbing. But when an Indian’s grave is dug up, it’s called archaeology.” These words, spoken by Tohono O’odham of American Indians Against Desecration, point to the conflict at the heart of Chip Colwell’s “Plundered Skulls and Stolen Spirits,” a careful and intelligent chronicle of the battle over Indian artifacts and the study of Indian culture.

After the Civil War, Mr. Colwell tells us, America’s scientists and anthropologists, funded by the U.S. government, collected millions of religious objects, cultural artifacts and human remains from Indian tribes with the plan of studying and exhibiting them. In 1879, Congress formed the Bureau of Ethnology, whose goal, Mr. Colwell writes, was to “document fading lifeways and gather cherished objects before they were forever gone.” The assumption was that Indian culture would disappear—either through assimilation or population decline—within a few years.

In some cases, items were recovered through trickery and even robbery. As George Dorsey, the first Ph.D. in anthropology at Harvard and a curator of Chicago’s Field Museum, explained in 1900 to one of his assistants: “When you go into an Indian’s house and you do not find the old man at home and there is something you want, you can do one of three things: go hunt up the old man and keep hunting until you find him; give the old woman such price for it as she may ask for it running the risk that the old man will be offended; or steal it. I tried all three plans and I have no choice to recommend.”

Mr. Colwell, a senior curator at the Denver Museum of Nature & Science, shows that not every researcher was as potentially unethical as Dorsey. Indeed, hundreds of thousands of objects now in museums like the Smithsonian or the Peabody Museum at Harvard or Mr. Colwell’s own Denver museum were purchased fairly. Native American tribes were often in financial straits—in some cases, tribe members needed the money for food and other necessities. So when dealers came to them offering to buy artifacts, they were happy to make a deal.

But ethical quandaries were unavoidable. As Mr. Colwell notes, “most transactions were inherently unequal, with cash and power in the hands of dealers and collectors, who rarely obtained the consent of all clan members.” Complicating matters, the communal ownership of artifacts often meant that the Native Americans who were making the deals didn’t really own the objects they were selling.

https://www.wsj.com/articles/native-american-exhibitions-1489179117