Art Forgeries Spring 2018

1. Where Art Forgeries Meet Their Match

By Anita Gates

May 2, 2018

Jamie Martin has some advice for criminals: “Never wear synthetic fibers while making a forgery.” They’ll show up in the lab.

And everybody knows that Vermeer didn’t wear polyester.

Mr. Martin shared that wisdom while showing a guest around his fifth-floor laboratory-office at Sotheby’s New York on the Upper East Side of Manhattan. It’s a large, windowless white room filled with technology, some of the equipment owned by only a handful of institutions worldwide.

Just past the locked door, with its laser-radiation danger warning, cameras were aimed at the vibrant oils of a Flemish old master. Mr. Martin described another painting in his office, seen only from the back, as “probably from the 16th century.” (The owners had not given him permission to show it.)

Mr. Martin, one of those lucky men who still look boyish in their late 50s, knows some forgers are careless, like the man whose supposed Jackson Pollock was sold to the Knoedler Gallery in Manhattan with the signature “Jackson Pollok.” That was part of a major 2016 art-world scandal, which Mr. Martin discussed on “60 Minutes.”

But some forgers are clever. They are the ones who fear Mr. Martin, who was called “the rock star of his field” with “no equal” in a recent Art New England article. After decades of consulting for the F.B.I., museums, auction houses and other clients, Mr. Martin is now head of Sotheby’s scientific research department. In its first year, 2017, his department examined works valued at more than $100 million, Darrell Rocha, a Sotheby’s spokesman, said.

Museums may have this kind of setup, but until now major auction houses didn’t. Sotheby’s acquired Orion Analytical, Mr. Martin’s Williamstown, Mass., company, in December 2016 and now claims 80 percent of his time, half of which he spends in New York and half either at Sotheby’s London or traveling, sometimes to examine artworks on site.

When a work comes to Mr. Martin, it begins a multipart analysis with an appraisal in visible light. Then, when he shines a bright light on the work, he can detect the presence of any optical brightening agents. Those were introduced around 1950, so if the work is supposedly older, that’s the end of that. With a black light, otherwise invisible cracks may be visible. In this Flemish old master, Adriaen Isenbrandt’s “The Flight Into Egypt,” one goes right through the Virgin Mary’s neck. Under black light, certain areas look very dark; that’s where the work has been restored.

With a shortwave infrared camera (the kind used in drones, Mr. Martin points out), you may see the artist’s underdrawing — the genius’s equivalent of a paint-by-number pattern. The lab’s second camera is less sensitive, he said, “but it sees through some things the other doesn’t.” The next step is an X-ray, done on site by an outside firm.

There’s a human factor too — in fact, a building full of veteran art specialists to consult. One told him that the “Flight Into Egypt” underdrawing looked very much like one in Isenbrandt’s crucifixion triptych at a museum in Estonia.

Mr. Martin strives for objectivity. “I don’t have any skin in the game,” he said, adding that his contract forbids bonus pay. He compared himself to an umpire, trying to make the right call.

But he does love watching the game. Asked whether he was more excited by finding a fake or confirming something as the real thing, he spoke slowly and chose his words carefully. “I get more excited when in working with other specialists we find physical evidence to support the attribution and the age.”

Mr. Martin, it turns out, does not declare authenticity. Although he has testified as an expert witness in a number of court cases, he will never be the guy who takes the stand and announces, “Yes, this is a Rembrandt!” or “This is a shoddy fake!” He answers just one question: Are there any contraindications to the claim?

For example? “We didn’t find anything inconsistent with Léger working in 1913.”

His reference is to “Dessin Pour ‘Contraste de Formes No. 2,’” believed to have been done by Fernand Léger (born 1881) in his early 30s. . It is part of a collection formed by Dr. Martin S. Weseley, a surgeon who died last year.

There, in his office, is a mosaic of its image on the screen of a seemingly standard laptop computer, where Mr. Martin uses the periodic table of elements to determine composition.

Aha, there’s calcium. That makes sense; one of the dominant paint colors in that era was bone black. (Bone equals calcium.) The whites consistently show lead and barium, which is exactly what was used in paint formulations then. Any titanium white? No. Good, because it was used only from the 1920s on.

Against one wall is the Bruker M6 Jetstream, about the size and shape of a big flat-screen TV and its stand. It examined the Léger by macro X-ray fluorescence (MA-XRF), making an astounding 1.2 million measurements overnight. Then the findings are confirmed with other analytical methods like Raman or Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy. The investigation goes deep, all the way to molecular analysis.

Growing up in Baltimore, Mr. Martin loved science and art equally, so he decided to study medical illustration at Johns Hopkins University. On his way to apply, though, he stopped at a Baltimore museum, where he bumped into (literally, as in “Sorry, was that your foot?”) a conservator. She offered him a backstage tour, after which Mr. Martin changed his plans (“I never made it to Johns Hopkins”). Eventually he was a postgraduate fellow in paintings conservation at Cambridge University. But early interests stuck; his narration abounds in medical metaphor.

If Sotheby’s were a hospital, his department would be “the E.R. or a clinic,” he said. One analysis is like an M.R.I., and another is like a CT scan. He described analyses as “noninvasive.” Mr. Martin tried to keep the discussion understandable to nonscientists, even comparing one device to a “Star Trek” phaser, but he also said things like: “Each one of the million pixels has its own spectrum.”

No scientific terminology is needed to explain Mr. Martin’s professional raison d’être. In an era when the very definition of facts is in flux, he’s after truth.

“I like living within the four corners of what’s right and what’s wrong.” he said, adding that he told people who work for him, “ ‘If you ever lie to me, you’re gone.’ ”

Correction: May 1, 2018

An earlier version of this article misstated the ownership of “Dessin Pour ‘Contraste de Formes No.2,’” believed to have been painted by Fernand Léger. It was part of the collection of Dr. Martin S. Weseley; it does not belong to the Berkshire Museum.

A version of this article appears in print on May 2, 2018 in The International New York Times. Order Reprints | Today’s Paper | Subscribe

https://www.nytimes.com/2018/05/02/arts/art-forgeries-sothebys.html

2. French museum's collection mostly fake, but is it the only one?

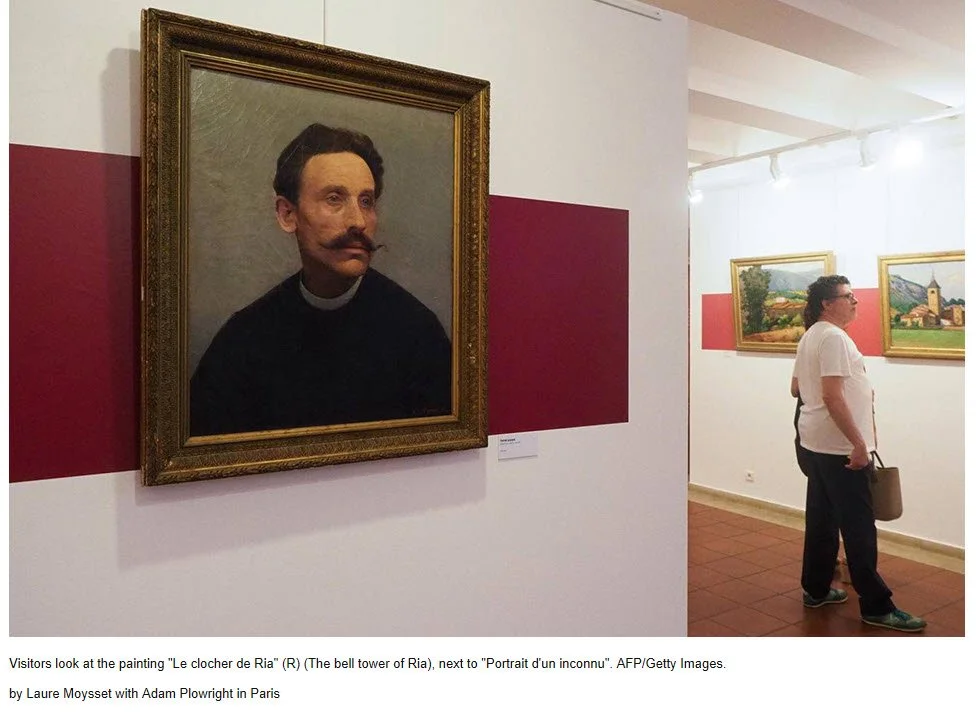

ELNE (AFP).- Over decades, the small museum of Elne in southern France built up a collection of works by local painter Etienne Terrus, mostly oil and watercolours of the region's distinctive landscapes and buildings.

But what was once a source of pride has turned to embarrassment after 60 percent were found to be fakes, providing a lesson about the dangers of buying art without expert skills and the ubiquity of counterfeit canvases.

"Etienne Terrus was Elne's great painter. He was part of the community, he was our painter," lamented mayor Yves Barniol on Friday as he reopened the museum and its exhibition of Terrus paintings -- minus the forgeries.

"Knowing that people have visited the museum and seen a collection most of which is fake, that's bad. It's a catastrophe for the municipality," he added.

Terrus (1857-1922) was born and died in Elne near the city of Perpignan where he painted the sun-baked Mediterranean coastline as well as the misty foothills of the Pyrenees mountains and local red-tiled homes.

While once a friend of Henri Matisse, Terrus never reached the heights of fame achieved by his contemporary, but he earned a following in art circles and regionally with his Impressionist- and Fauvist-influenced production.

The Terrus Museum in Elne began collecting his work in the 1990s and went on a spending splurge over the last five years, acquiring 80 new canvases often thanks to local fund-raising drives.

Devastated locals who helped with the effort now regret being so naive, having handed over tens of thousands of euros to local art dealers and private collectors.

Out of 140 works owned by the museum, 82 were judged to be fakes by a panel of experts, causing an estimated loss to the town of 160,000 euros ($200,000).

A global problem

But art-testing expert Yan Walther says fake art being exhibited publicly is a problem worldwide and the case of Elne, though extreme, is not unique.

"The fact that there are fakes and misattributed works in museum collections is something absolutely clear and nobody with an understanding of the field has any illusions about this," Walther told AFP.

"There are misattributed works in the Louvre (in Paris) in the National Gallery (in London), all museums in the world, but it is not in a proportion like 60 percent," he added.

A state museum in the Belgian city of Ghent was accused of exhibiting fakes in January after it put 26 works supposedly by Russian avant-garde artists such as Kazimir Malevich and Wassily Kandinsky on display.

Many experts questioned how the paintings -- the private collection of Russian businessman Igor Toporovski -- could have been amassed in secret and the museum had to cancel the show amid a police investigation.

Walther's company, Swiss-based SGS Art Services, is a world leader in using scientific methods such as X-rays and carbon-dating to help authenticate art works.

SGS mostly tests high-end paintings worth between 50,000 and sometimes tens of millions of euros and Walther says on average a staggering 70-90 percent are found to be fake or misattributed.

Misattribution can mean, for example, that a painting was produced by the workshop or assistant to an artist.

"When you acquire real estate or a car, there are a certain number of steps everyone would take: a technical assessment, background checks on the seller," he said.

"For art work, very strangely it is still not in people's minds. You can buy a an artwork for two million dollars and people hardly check anything. But it is starting to change."

Crude fakes

The fraud in Elne was discovered by local art historian Eric Forcada who said he had seen the problems immediately, with some of the paintings crude counterfeits.

"On one painting, the ink signature was wiped away when I passed my white glove over it," he said.

In another painting, there was a building that was completed in the 1950s -- 30 years after Terrus's death -- while some of the canvases did not match those used by the original painter.

Forcada alerted the region's top cultural expert and requested a meeting of a panel of experts to confirm his findings.

A police investigation is now set to focus on local art dealers who were the source of many of the paintings.

"The whole of the local art market is rotten, from the unofficial street vendors who pitch to local private collectors up to the art dealers and the auction houses," Forcada said.

Prior to the scandal, paintings by Terrus could fetch up to 15,000 euros ($18,200) and drawings and watercolours would sell for up to 2,000 euros, he said.

l

© Agence France-Presse

http://artdaily.com/news/104285/French-museum-s-collection-mostly-fake--but-is-it-the-only-one-#.WxWONkxFxaQ