Archaeology - Summer 2020

1. JORDAN Do These 10,000-Year-Old Flint Artifacts Depict Human Figures? By Alex Fox SMITHSONIANMAG.COMJULY 16, 2020New research suggests 10,000-year-old flint artifacts found at a Neolithic burial site in Jordan may be human figurines used in a prehistoric cult’s funeral rituals. If confirmed, the trove of more than 100 “violin-shaped” objects would be one of the Middle East’s earliest known examples of figurative art, reports Ariel David for Haaretz.A team of Spanish archaeologists unearthed the mysterious artifacts at the Kharaysin archaeological site, located around 25 miles of the country’s capital, Amman. The layers in which the flints were found date to the eighth millennium B.C., the researchers write in the journal Antiquity.The study hypothesizes that the flint objects may have been “manufactured and discarded” during funerary ceremonies “that included the extraction, manipulation and reburial of human remains.”Juan José Ibáñez, an archaeologist at the Milá and Fontanals Institution for Humanities Research in Spain, tells New Scientist’s Michael Marshall that he and his colleagues discovered the proposed figurines while excavating a cemetery. Crucially, Ibáñez adds, the array of flint blades, bladelets and flakes bear no resemblance to tools associated with the Kharaysin settlement, which was active between roughly 9000 and 7000 B.C. Per the paper, the objects lack sharp edges useful for cutting and display no signs of wear associated with use as tools or weapons. The majority of the figurines are made of flint, but archaeologists also found several clay artifacts. (© Ibáñez et al / Kharaysin archaeological team / Antiquity Publications Ltd)Instead, the flints share a distinctive—albeit somewhat abstract—shape: “two pairs of double notches” that form a “violin-shaped outline,” according to the paper The scientists argue that the artifacts’ upper grooves evoke the narrowing of the neck around the shoulders, while the lower notches are suggestive of the hips. Some of the flints, which range in size from 0.4 to 2 inches, appear to have hips and shoulders of similar widths; others have wider hips, perhaps differentiating them as women versus men.“Some figurines are bigger than others, some are symmetrical and some are asymmetrical, and some even seem to have some kind of appeal,” study co-author Ferran Borrell, an archaeologist at Spain’s Superior Council of Scientific Investigations, tells Zenger News’ Lisa-Maria Goertz. “Everything indicates that the first farmers used these statuettes to express beliefs and feelings and to show their attachment to the deceased. ”When the researchers first discovered the fragments, they were wary of identifying them as human figurines. Now, says Ibáñez to Haaretz, “Our analysis indicates that this is the most logical conclusion. ”Still, some scientists not involved in the study remain unconvinced of the findings. Karina Croucher, an archaeologist at the University of Bradford in England, tells Live Science’s Tom Metcalfe that prehistoric humans may have used the flint artifacts to “keep the dead close” rather than as a form of ancestor worship. Speaking with New Scientist, April Nowell, an archaeologist at Canada’s University of Victoria, says the team’s hypothesis intrigues her but notes that “humans are very good at seeing faces in natural objects.”She adds, “If someone showed you that photograph of the ‘figurines’ without knowing the subject of the paper, you would most likely have said that this is a photograph of stone tools.”Alan Simmons, an archaeologist at the University of Nevada, tells Live Science that interpreting the flint pieces as representing the human figure is “not unreasonable” but points out that “the suggestion that these ‘figurines’ may have been used to remember deceased individuals is open to other interpretations.”Theorizing that the flints might have been tokens, gaming pieces or talismans, Simmons concludes, “There is no doubt that this discovery adds more depth to the complexity of Neolithic life.”https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/10000-year-old-flint-objects-may-be-human-figurines-180975325/?utm_source=smithsoniandaily&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=20200716-daily-responsive&spMailingID=42975042&spUserID=NzQwNDU3ODAxODcS1&spJobID=1801242530&spReportId=MTgwMTI0MjUzMAS22.

JABAL MARAGHA (AFP).- When a team of archaeologists deep in the deserts of Sudan arrived at the ancient site of Jabal Maragha last month, they thought they were lost. The site had vanished. But they hadn't made a mistake. In fact, gold-hunters with giant diggers had destroyed almost all sign of the two millenia-old site. "They had only one goal in digging here -- to find gold," said shocked archaeologist Habab Idriss Ahmed, who had painstakingly excavated the historic location in 1999."They did something crazy; to save time, they used heavy machinery."In the baking-hot desert of Bayouda, some 270 kilometres (170 miles) north of the capital Khartoum, the team discovered two mechanical diggers and five men at work.They had dug a vast trench 17 metres (55 feet) deep, and 20 meters long.The rust-coloured sand was scarred with tyre tracks, some cut deep into the ground, from the trucks that transported the equipment. The site, dating from the Meroitic period between 350 BC and 350 AD, was either a small settlement or a checkpoint. Since the diggers came, hardly anything remains. "They had completely excavated it, because the ground is composed of layers of sandstone and pyrite," said Hatem al-Nour, Sudan's director of antiquities and museums." And as this rock is metallic their detector would start ringing. So they thought there was gold. "Escape justice Next to the huge gash in the ground, the diggers had piled up ancient cylindrical stones on top of each other to prop up a roof for their dining room. The archaeologists were accompanied by a police escort, who took the treasure-hunters to a police station -- but they were freed within hours. "They should have been put in jail and their machines confiscated. There are laws," said Mahmoud al-Tayeb, a former expert from Sudan's antiquities department Instead, the men left without charge, and their diggers were released too."It is the saddest thing," said Tayeb, who is also a professor of archaeology at the University of Warsaw. Tayeb believes that the real culprit is the workers' employer, someone who can pull strings and circumvent justice. Sudan's archaeologists warn that this was not a unique case, but part of a systematic looting of ancient sites. At Sai, a 12-kilometre-long river island in the Nile, hundreds of graves have been ransacked and destroyed by looters. Some of them date back to the times of the pharaohs. Sudan's ancient civilisations built more pyramids than the Egyptians, but many are still unexplored. Now, in hundreds of remote places ranging from cemeteries to temples, desperate diggers are hunting for anything to improve their daily lives. Gold fever Sudan is Africa's third largest producer of gold, after South Africa and Ghana, with commercial mining bringing in $1.22 billion to the government last year.In the past, people also tried their luck by panning for gold at the city of Omdurman, across the river from Khartoum, where the waters of the White and Blue Niles meet ."We used to see older people with small sieves like the ones women use for sifting flour at home," Tayeb said, recalling times when he was a boy. "They used them to look for gold. "But the gold they found was in tiny quantities. Then in the late 1990s, people saw archaeologists using metal detectors for their scientific research. "When people saw archeologists digging and finding things, they were convinced there was gold."' Reason for pride 'Even worse, local authorities have encouraged the young and unemployed to hunt for treasures while wealthy businessmen bring in mechanical diggers alongside. "Out of a thousand more or less well-known sites in Sudan, at least a hundred have been destroyed or damaged," said Nour. "There is one policeman for 30 sites... and he has no communication equipment or adequate means of transport "For Tayeb, the root problem is not a lack of security, but rather the government's priorities ."It's not a question of policemen," he said. "It is a serious matter of how do you treat your history, your heritage? This is the main problem. But heritage is not a high priority for the government, so what can one do?" The destruction of the sites is an extra tragedy for a country long riven by civil war between rival ethnic groups, destroying a common cultural identity of a nation ."This heritage is vital for the unity of the Sudanese," Nour said. "Their history gives them a reason for pride."https://artdaily.cc/news/118608/Gold-hunting-diggers-destroy-Sudan-s-priceless-past#.X2o_r2hKhsA

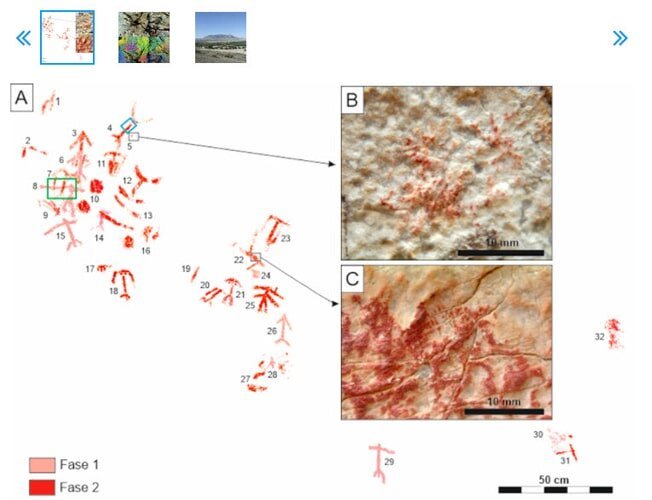

3. SPAIN Some 7,000 years ago, prehistoric humans added red ocher paintings to Los Machos, a natural rock shelter in southern Spain. The drawings appear to depict people, geometric motifs and scenes from daily life, reports Garry Shaw for the Art Newspaper. But the artists didn’t sign their work, so archaeologists have turned to fingerprint analysis to learn more about who they were.A new study published in the journal Antiquity pinpoints two potential painters: a man who was at least 36 years old and a juvenile girl aged 10 to 16 years old.To identify these ancient artists, the researchers compared fingerprints found at Los Machos to modern ones made by individuals of a known age and sex. Per the Art Newspaper, men’s fingerprints tend to have broader ridges than women’s, and as a person grows older, the distance between the ridges in their fingerprints increases. “We looked at the number of fingerprint ridges and the distance between them and compared them with fingerprints from the present day,” lead author Francisco Martínez Sevilla, an archaeologist at the University of Granada, tells the Guardian’s Sam Jones. “Those ridges vary according to age and sex but settle by adulthood, and you can distinguish between those of men and women. You can also tell the age of the person from the ridges. ”The findings suggest that cave painting was a social activity, not an independent one as previously thought. They also support earlier research indicating that cave painting wasn’t a male-dominated practice. As the Art Newspaper notes, a recent analysis of hand stencils left behind by Paleolithic cave painters showed that women created around 75 percent of rock art in French and Spanish caves .Described in a press release as the first application of fingerprint analysis in assessing rock art, the study nevertheless leaves some questions unanswered: for instance, the nature of the pair’s relationship, whether the two artists were from the same community and why they painted the red ocher shapes on the cave walls, as Martínez Sevilla tells the Guardian. Margarita Díaz-Andreu, an archaeologist at the University of Barcelona who wasn’t involved in the study, deems it an “exciting proposal” but points out that the fingerprints analyzed may not have belonged to the cave painters themselves .“We know that in several societies in the world, the people who were in charge of painting were often accompanied by other members of the community,” Díaz-Andreu tells the Art Newspaper. Overall, says Leonardo García Sanjuán, a prehistory expert at the University of Seville who also wasn’t involved in the research, the researchers’ method of fingerprint analysis has great potential for the study of other rock art sites in Spain. “The analysis of fingerprints in terms of sex and age is a great contribution towards understanding who was involved in the production of rock art,” García Sanjuán tells the Art Newspaper, adding that with a larger array of fingerprints and art sites, researchers may be able to form a clearer picture of which community members were most involved with rock art creation. Artwork-adorned rock shelters are scattered across Spain. In 1998, Unesco collectively declared more than 700 such sites a World Heritage Site .Of the Los Machos rock shelter, Martínez Sevilla says, “The area where they are, and the fact that they haven’t been changed or painted over, gives you the feeling that this was a very important place and must have had a really important symbolic value for this community.”https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/fingerprints-rock-art-reveal-new-information-about-prehistoric-artists-180975849/?utm_source=smithsoniandaily&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=20200918-daily-responsive&spMailingID=43495876&spUserID=NzQwNDU3ODAxODcS1&spJobID=1841576192&spReportId=MTg0MTU3NjE5MgS2